Researcher poses two scenarios for Nunavut gold mine closure

“People are actually left with mining skills, but not with other skills once the mine closes”

Annabell Rixen speaks to an audience of academics, students, policy makers and others at ArcticNet’s Arctic Change conference Dec. 12 at the Ottawa Conference Centre. (PHOTO BY DAVID MURPHY)

The 1,800-person community of Baker Lake has less than three years to go before the Meadowbank gold mine, about 100 kilometres from the town, closes down.

Until then, questions linger about how Nunavut’s only inland hamlet can support itself afterwards, problem free.

“People said overwhelmingly that — with the mine closing in 2017 — there is very little awareness and very little preparedness for that scenario,” said Annabell Rixen, a master’s student assessing the mine closure and community preparedness as part of a project called “Tuktu.”

Rixen’s presentation was part of the four-day Arctic Change conference, hosted by ArcticNet, which unfolded Dec. 8 to Dec. 12 at the Ottawa Conference Centre.

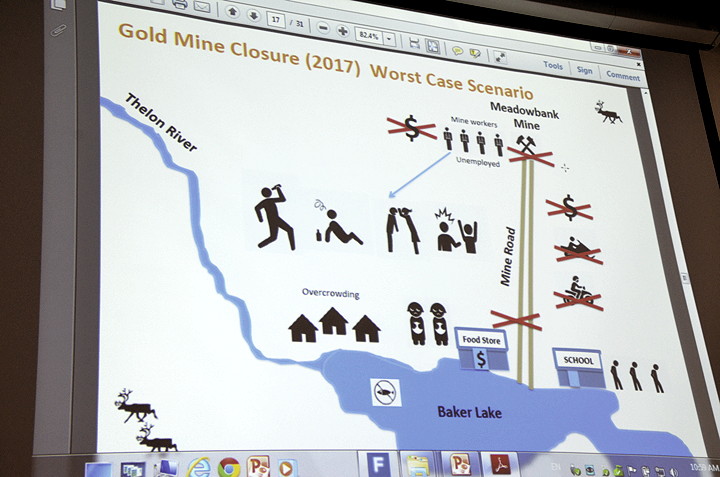

Rixen boiled her research down to two visions: a worst and best-case scenario.

The best case: job training programs are implemented to stimulate new local businesses and money is injected into mental health, childcare and cultural programming. Also, dwindling caribou numbers return to full strength.

“As the elders emphasized: let our land recover. We need to give our land the proper time to rejuvenate,” Rixen told Nunatsiaq News.

The worst case scenario: there’s no money for any of those programs, domestic fighting and alcohol abuse rise, and the caribou don’t come back to town.

The study, which first began in 2009, is the result of discussions and interviews with locals in Baker Lake. The residents also analyzed the results to create findings for the report.

Rixen says she’s an optimist about the mine closure.

“I am a lot more optimistic, because we are seeing a lot more people now respond very well to people planning ahead,” she said.

Agnico Eagle, which runs the Meadowbank gold mine, has also been open with her and the community so that they “leave a positive legacy in this community,” Rixen said.

“I hope they remain that open in the upcoming year as well,” she said.

But there are still many unanswered questions.

“People are actually left with mining skills, but not with other skills once the mine closes,” Rixen said.

“The caribou are already far from town. The store prices of foods actually rose since the mine’s appearance,” she said.

“[Residents] are saying right now, we have insufficient mental health staff to help us deal with challenges coming up. We have insufficient child care spaces.”

Areva Resources, which hopes to open the Kiggavik uranium mine outside of Baker Lake as early as 2018, is another story.

Rixen said people of Baker Lake, about 80 km east of the proposed mine, are finding a lack of transparency from the company.

“When we are trying to construct the uranium mine scenario, people are saying, well, we can’t really construct anything because we don’t have enough information,” she said.

The Nunavut Impact Review Board has so far granted eight groups intervener status for upcoming final hearings over Kiggavik’s Final Environmental Impact Statement scheduled to take place in Baker Lake from March 2 to March 20, 2015.

Those interveners include the Hamlet of Baker Lake, the Beverly Qamanirjuaq Caribou Management Board and Nunavummiut Makitagunarningit, a non-governmental organization concerned about the cumulative impacts uranium mining could have on people and wildlife.

Those concerns might be warranted.

On top of a lack of transparency, Rixen said she’s heard accounts from elders and hunters that Areva has violated some caribou protection measures by drilling with caribou nearby — something they’re not supposed to do.

“According to accounts, there have been mining workers in the past who observed that they have not stopped drilling operations. They were at first, but they were kind of getting sick of stopping every time there was a caribou nearby,” Rixen said.

When it comes to the uranium mine, Rixen turns from optimist to pessimist.

“I doubt that a project constructed on caribou post-calving grounds can have a long lasting, sustainable impact,” she said.

“I’m asking: where is the sustainable impact if you’re constructing on a site that’s essential for that population, that’s essential for local livelihood?”

The community is still divided over uranium mining, however. It’s not as simple as saying the people of Baker Lake prioritize caribou over mining development, or vice versa.

“You have some families that are heavily dependent on the mine, you have other families that are completely in opposition to mining development,” Rixen said.

“There isn’t one joint perspective. I think the obvious thing we know about communities in the North is that young people want jobs and so mining gives them one opportunity,” she said.

“At the same time people want their country food and they still rely on wildlife resources.”

One former Baker Lake resident at the presentation said it’s hard to find a balance between preserving the Inuit culture and embracing mining life in the community.

Sally Webster moved from Baker Lake to Ottawa in 2002 but she still speaks to elders in Baker Lake. They say family members who work at Meadowbank are too tired to hunt animals for elders after their shifts.

“[The elders] said they should be hunting for us. Although they’re making fast money […] but elders are hungry. Because they want country food,” Webster said.

And a lack of country food might have health consequences for younger generations to come.

“If they stop eating country food, we could see in the future that they are going to have a lot of diabetes,” Webster said.

The NIRB’s public hearings on Areva’s final EIS will have both technical and more casual components.

Technical presentations are planned for March 2 to March 7, 2015 at the Baker Lake Community Center and community roundtables are scheduled for March 9 to March 15. The agenda for the final four days has not been determined yet.

An infographic from Annabell Rixen’s presentation at the Arctic Change conference shows a possible worst case scenario in Baker Lake when the Meadowbank gold mine closes down in less than three years: loss of money and jobs and the potential for crime, addiction and family violence. (PHOTO BY DAVID MURPHY)

(0) Comments