Stalling on polar shipping code spells disaster, says IPY conference panel

Move to approve international Polar Code moves ahead at a “glacial pace”

The Arctic Council wants to ensure safer shipping activity in the Arctic, says Gustaf Lind, chairman of the Arctic Council April 24 at the International Polar Year conference in Montrea. Sweden, which now chairs the Arctic Council, passes leadership to Canada in 2013. (PHOTO BY JANE GEORGE)

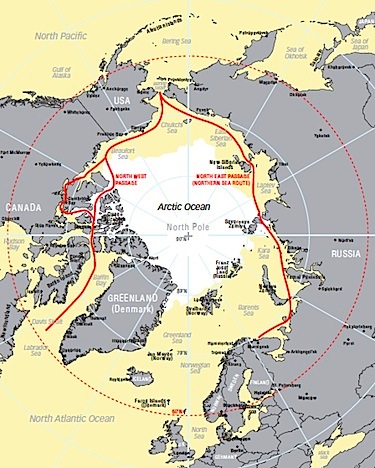

This map from a recent report by the insurance company Lloyd’s shows the Arctic shipping lanes where many want to see a Polar Code regulating marine traffic.

MONTREAL — No lives have been lost yet in Arctic shipping mishaps, and everyone managed to get off the shoaled Clipper Adventurer when it hit a rock in Nunavut’s Coronation Gulf two years ago — but there’s little to prevent marine traffic catastrophes from taking place in Arctic waters, say experts at the International Polar Year conference in Montreal.

The International Marine Organization, the United Nations body tasked with developing shipping regulations among 167 nations, is dragging its feet on enacting a new Polar Code for ships in the Arctic, said panelists at an April 24 discussion of Arctic shipping.

This Polar Code would tighten up regulations about what kinds of ships can travel in the Arctic and set other rules for operations to improve safety.

But the move to establish a Polar Code is progressing at a “glacial place,” speakers at the panel said.

They say the world’s shipping industry needs to stop its “reactive” way of dealing with Arctic marine disasters, which sees industry and authorities reacting to emergencies as these happen rather than moving to prevent them from occurring in the first place,

During the panel discussion, Dugald Wells, founder of Cruise North Expeditions with Makivvik Corp., pointed to a basic disconnect between what tourists want and marine safety in the Arctic.

“Exploration is at odds with rules and regulations which is about standards and safety,” he said.

Pilots learn to avoid ice “but what tourists want to see is the ice.” As well, tourists go on Arctic cruises for that “first ever” feeling of exploration while pilots want on be on time safely for the next place.

“A ship’s captain finds himself in all kinds of situations,” Wells said.

Cruise traffic throughout the Arctic region also worries Lawson Brigham, a shipping and Arctic policy expert from the University of Fairbanks, Alaska, particularly when he learns about a cruise ship travelling to the Arctic from Miami, without the needed Arctic safety equipment and experienced ice pilots.

As for the Polar Code, if the Arctic is “lucky” it maybe see a Polar Code for 2014 or 2015, Brigham said.

Earlier this year, the members of the IMO decided decided to postpone the development of the environmental section of the Polar Code on shipping until 2013.

The IMO took the move due to procedural objections by mostly non-polar states and the industry lobby.

Now “the onus is on the Arctic states to put pressure on” to get the Polar Code enacted, Brigham said.

But it’s not just cruise ships that cause concern in the Arctic: it’s the growth of industrial traffic.

Arctic cruise voyages through 2020 now go from point “a” to point “b,” rather than trans-Arctic, that is, across the circumpolar region.

But huge mining projects like the Mary River iron project want start tanker traffic through the Canadian Arctic — and there’s already an increasing amount of industrial shipping along the Northeast Passage, across the top of Russia.

Insurance companies, such as Lloyds of London, say governments need to build more infrastructure and search and rescue capability to enable safe economic activity, said a marine lawyer at the IPY conference panel discussion.

And, there’s some urgency, Lloyds noted in a recent report.

That’s because, as Arctic sea ice retreats and thins, Arctic shipping without icebreaker support is likely to take place for longer periods of the year, and ultimately all year round, in some parts of the Arctic.

Canada introduced stiffer pollution-prevention regulations for Arctic waters in 2009, doubling to 370 kilometres the offshore distance over which Canadian rules would apply.

And, also since 2010, a ship-tracking regime, called the Northern Canada Vessel Traffic Services Zone, regulates the movement of cargo carriers, cruise ships and other large vessels moving through the Northwest Passage and throughout the waters of the High Arctic islands.

Some have suggested that the Arctic Council should embrace a multilateral treaty of Arctic regional states to implement its own maritime “polar code” and other requirements on shipping.

That’s something that the Arctic Council could move on, the Swedish chairman of the Arctic Council Gustaf Lind said during a conference panel on adaptation to change.

The Arctic Council produced a report on Arctic shipping in 2009, which called for action to improve Arctic shipping, it approved a binding agreement on search and rescue last May, and the council also moving ahead with an agreement on oil and gas spill response and a survey of Arctic ports and airports.

In 2013, the Arctic Council chair passes back to Canada.

(0) Comments